(12/21/20) viral memes and developing taste

What I learned from hundreds of hours of watching blog posts go viral

I got my first job in the startup world after I cold emailed the founder of a blog I really liked.

The blog, Priceonomics, was a Y Combinator-backed journalism “startup” (I didn’t know what that meant at the time).

Around 2013, this four-person ensemble regularly went viral without intending to, their longform pieces getting picked up by the New York Times, Wired, Business Insider, Digg, Reddit, Hacker News, and many others.

Their founder wanted to experiment with different types of content. Could they drive the same quality of traffic with shorter and more frequent pieces?

So my charge was to answer that question. I wouldn’t say I did a great job figuring that out. But I did learn the mechanics of something that has stuck with me since — The Zimmerman Effect.

How a Meme Goes Viral

My typical day at the Priceonomics office looked like this:

Heat up water and prepare the coffee beans for my pourover.

While sipping on that naughty dark nectar, noodle on unfinished drafts for future pieces.

Sit with the head writer and rework the two pieces I was slated to publish that day.

Stare at my feed of new posts being published by obscure-ish blogs on the Internet.

Through #4, I learned how the cultural zeitgeist is created online. In real-time, I witnessed the rise and fall of memes and ideas. Here’s an example.

Monday:

Morning: the National Bureau of Economic Research publishes a new study.

Afternoon: a statistics professor and small Twitter account share that study along with some brief thoughts on it. Their social media followers give these posts some love.

Tuesday:

Lunchtime: A more popular blogger, who may have seen the professor’s post on Facebook or Twitter, links to the professor’s post, but tweaks the language for his audience — throws in a pretty chart as well. Even more social media followers share this piece.

Wednesday:

Early morning: the popular blogger’s post ends up on a popular subreddit.

Late morning: it’s on the front page of Hacker News.

Evening: a midsized media outlet like The Intercept writes about it.

Thursday:

All day: it’s on Huffington Post, The Guardian, and ABC News Australia. For a brief moment in time, it’s everywhere. Your grandpa probably scrolled right by it on Facebook.

Friday:

The piece is dead.

Sometimes, the single cycle completed in the span of 12 hours. Sometimes over a few weeks. 99% of the time, the cycle would end before it could even start.

The Zimmerman Effect

Watching all this transpire every week for many different stories was like peeking into The Matrix. A small nugget of content clings onto something slighter bigger above it, shape-shifting enough to cling onto even bigger and bigger. But it was hard to predict which nugget would take the ride and for how long.

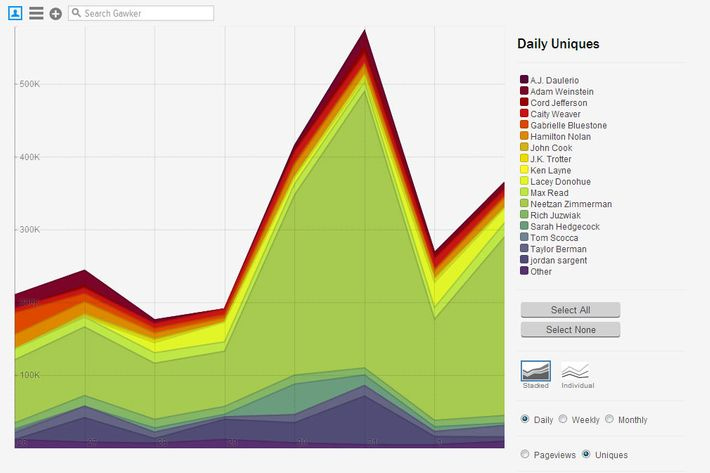

Neetzan Zimmerman of the now-defunct Gawker figured out how to harness this phenomenon.

Zimmerman built a system to track the flow of content from small blog to slightly bigger blog to very big outlet.

The idea, as I wrote several years ago, was:

to take content that had already demonstrated strong appeal to a smaller audience, and then to give that content the right “push” (packaging and distribution) for it to go viral.

Zimmerman found promising little seeds gaining steam (like the cuddly cat above). He would then carefully write and rewrite the title for maximum catchiness. His posts consistently topped Gawker’s internal leaderboard for most page views.

Behold, the Zimmerman Effect. Bottle up lightning right before you see the sparks fly.

Sometimes when you learn how the sausage is made, you never want to eat sausage again.

I felt that way while interning at a PR firm, where I pitched Forbes to put the firm’s clients on the “30 Under 30” list. That’s one way to play the game, but that doesn’t mean I have to like it.

I felt similarly when I learned about the Zimmerman Effect.

If your business model relies on chasing viral hits, then I feel bad for you, your employees, your advertisers, and your audience. You’re trading in fifteen seconds of massive relevance right now for a likely disaster later.

If you’re chasing the RIGHT NOW appeal of the masses, you are at the whims of their extraordinary delusions. It reminds me of that Charles Mackay quip:

“Men, it has been well said, think in herds; it will be seen that they go mad in herds, while they only recover their senses slowly, one by one.”

Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (1841)

Gawker got sued and no longer exists. And remember Upworthy? That bright star faded away. Also, do you see what’s happening to mainstream media in 2020? 🤫

So no, the Zimmerman Effect didn’t show me the value of going viral (though there is a time and place for it). Quite the opposite. It sent me further upstream.

The best ideas tend to endure, even if they change their outer appearance from time to time. This is the basis of good taste.

You know how good chefs or designers or engineers can just look at something and say “yeah, [this is excellent | something is off]”? That master’s intuition for the way of things? It’s the discernment between what works right now vs. what works always.

You can train for this.

Zimmerman developed a taste for recognizing viral memes before they take off. His system helped him learn to intuit this.

But screw memes, we can develop a taste for our more inspiring personal pursuits — architecture, food, design, sports, and the million valuable niche interests sitting in the cracks.

To develop good taste, you first have to understand that every field has a sociology. It’s not just the ideas, it’s the people behind them.

There are those who produce the works, there are those who distribute the works, and there are those who do varying degrees of both. This is the structure of an information ecosystem.

The Information Ecosystem

The information ecosystem has two pressures pushing against it: Production and Distribution.

Production — the hard work of creating fresh ways of seeing the world.

Distribution — the hard work of getting the world to notice.

The producers are so focused on production, they may not have the time or interest to maximize distribution. It would be silly to say that producers don’t care at all about distribution — an empty gallery makes for an unfulfilled artist.

The distributors are so focused on exposure, they may not have the gumption or interest to be the ones producing. It’s hard to create something fresh if you’re looking at it with stale eyes. But without an eye for distribution, there is no sustained production.

As a result, you get some interesting dynamics forming:

At the very obscure, niche bottom, you have taste changers. They are hanging out with other producers. They’re running midnight shows together at small comedy clubs. They’re doing super wacky installations at warehouse parties in Bushwick.

Then you have taste makers. They’re the ones going to the wacky warehouse parties and random comedy shows. They’re probably amateur producers, too, and they might even be pretty good at producing themselves. But their primarily contribution here is their eye and their voice — they have an audience.

This audience we can call the taste takers. They love trying out new things, as long as it is sufficiently vetted by taste makers they trust. If a product doesn’t pass this filter, they will probably view it suspiciously or ignore it. They might also have some dabbling interest in production. But these taste adopters, when they love something, they really love it. They will tell all their taste adopter friends about it.

At the tail end of the spectrum are the taste breakers. They won’t try anything new unless others drag them out to try it. When a product gets to this point, it has matured and saturated the market.

The beauty of this structure is that if you want to dive deep into a field, you go to where the tastes are made.

Developing Taste

You may really love watching the Food Network. At some point, your love for shows like Chopped and The Great British Baking Show leads you to try some new things in the kitchen.

When you watch these shows again, you’ll quickly notice that a contestant’s dough is over proved. That another’s piping skills hold her back from great baking. You take these concepts with you as you notice your own work subject to them.

As you start attempting more and more ambitious techniques in the kitchen, you start diving deeper into the literature and technical practices. You learn which tools the pros use and who’s who in the field. The names Dan Barber and Rene Redzepi keep popping up. You figure out who they are, who influenced them, and what their contributions to food have been. The Production-Distribution value chain helps you deepen your interest.

This process is called developing taste. Training your senses.

Developing taste happens organically, but it seems to follow a pretty straightforward algorithm driven by curiosity.

Consume something of somewhat mass appeal.

Gather interest in it as you consume more things like it.

Try it out yourself.

Follow the references.

Keep trying things out yourself as you repeat #1-4.

Here’s a personal example: My own interest in hip-hop.

Between the ages of 16 and 24, I spent thousands of hours producing electronic music. It started with listening to Nas, Lupe Fiasco, and Rage against the Machine. It deepened with chasing liner notes and references to Eric B. & Rakim, DJ Premier, and Brian Eno. It transformed from appreciation to production when introduced to FL Studio and Native Instruments.

So when Kendrick Lamar released his first two studio albums, I fell in love with them. He was making fresh contributions to a creative lineage I was plugged into. His references, stories, and cadence were not accidental.

I became a fan for life. There was a relationship and appreciation there that went beyond noise coming out of headphones. I understood the work that went into making those sounds.

Good taste is the dual imperative of the earnest producer and the appreciative consumer. A strong connection forms between the two when the forces of the information ecosystem bring them together. So good taste is not about snobbery, it’s about relationship.

If we aren’t thinking about where the things we consume come from, we diminish our taste and thus become insatiable.

Nothing we consume seems to hold our interest, and so we consume more and more. Viral memes become less nuanced and more outrageous, if only to grab our fickle palettes more forcefully. Which leave us even less satiated.

Imagine what the culture becomes.

Ammar